The Monkees -

I'm A BelieverThe Young Rascals -

I've Been Lonely Too LongKeith -

98.6Procol Harum -

Whiter Shade of PaleThe Fifth Estate -

Ding Dong! The Witch Is DeadThe Tijuana Brass -

Casino RoyaleThe Choir -

(And Now) It's Cold OutsideLiving in a world with iTunes, ring tones, podcasts, streaming Internet radio, and satellite radio, it's hard to imagine depending on AM radio or a jukebox for exposure to new pop music. These are songs I will always associate with a particular jukebox, in a particular time and place, but also with what I've since learned was happening to pop culture that year.

Technically, for a month or so in the summer of 1967, my family was homeless. We'd left Mississippi, but couldn't move into our apartment in the NYC suburbs right away. So for a few legendary weeks, my mother, my brothers and I shared a small trailer, a tent, and a generous supply of insect repellent at a funny little camping ground near where my grandparents lived in Wisconsin, called Becker's Rest Cove. The center of social activity -- such as it was -- was a little recreation building with a canteen, a pool table, and a jukebox. A bunch of other songs would have been on the jukebox besides these I've listed, but I would already have been familiar with them, so those have other associations for me.

It's rare that cultural changes are as cataclysmic as they were between 1965 and 1969, and in 1967, those changes were in full swing. In San Francisco, the summer of '67 was "The Summer of Love". The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, often acknowledged to be the front edge of the cataclysm I'm talking about, was released. Jimi Hendrix started the year opening for the Monkees, and finished it a headliner.

For a while, in the time between Rubber Soul and The White Album, the Beatles were both the most popular group in the world and -- at least with us younger mass-pop consumers -- the ones pushing the envelope. Then the lesser-known influences that inspired them began to get their own recognition, and with the emergence of a musical and cultural underground -- aided by the emergence of "underground" (FM) radio -- critical acceptance and commercial success began to diverge. In the essential recurring irony of fashion, a form of cultural elitism became available to the masses, and that created a class distinction that could then be made between such "serious" artists as The Stones, Cream, Hendrix, etc., and other music deemed to be throwaway pop. It was about then that the term "Top-40" started to become a put-down.

[This class distinction wasn't necessarily observed by the artists themselves. For example, according to Mike Nesmith of the Monkees, he learned about Jimi Hendrix from John Lennon, over dinner with Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton.]

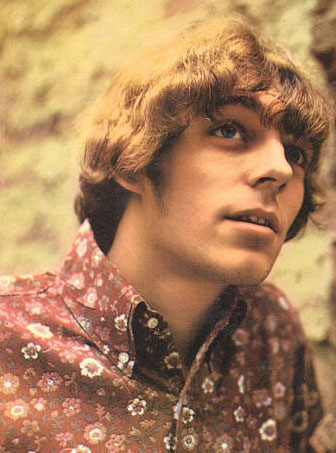

The Monkees

The Monkees

The Young Rascals had four U.S. top-20 songs in 1967. I've Been Lonely Too Long was the only one not to make the top ten during that year, reaching #16. Along with The Righteous Brothers, The Box Tops, etc., this white, mostly-Italian, NYC-area band helped popularize what became known as "Blue-Eyed Soul". They payed sincere homage to their Motown and Memphis contemporaries, with mixed results -- some of the Rascals' big hits have a kind of forced, ersatz soulfulness that doesn't wear well with time. Although it's less well-known, this record has a more genuine R&B flavor, and remains my favorite Rascals side.

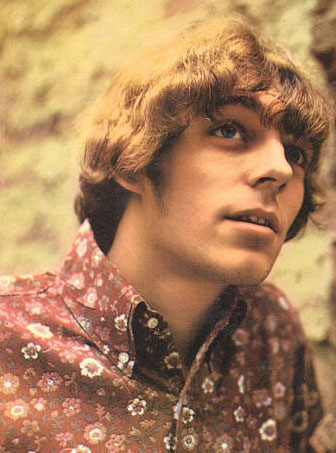

Keith

Keith

A Whiter Shade of Pale was a hit in Europe, #1 in the U.K., and made top ten in the States. In retrospect, Procol Harum had more affinity with the emerging "underground" artists of the day, and this song will always be one of those bizarre Top-40 anomalies that pepper the historical charts (a topic for another Friday Random Ten, perhaps). Its two hooks were its vaguely classical chord progression, which was like descending a stairway in an Escher drawing -- you go down and around and end up at the top somehow -- and the fact that its lyrics were obscure, if not completely undecipherable. My sixteen-year-old cousin -- also staying at the campground -- had managed a summer romance with one of the locals, and I remember them slow-dancing to this song. Years later, after casually dismissing Procol Harum as a "one-hit wonder", I was corrected by a college roommate, through whom I eventually became a fan. At its best, Procol Harum's music balanced a blues-based muscularity -- provided by guitarist Robin Trower and drummer B.J. Wilson in the original lineup -- with the structured classical elements from pianist and singer Gary Brooker and organist Matthew Fisher, and non-performing lyricist Keith Reid's inscrutable, often melancholy, sometimes playful lyrics.

The Fifth Estate, a Stamford, Connecticut garage band, recorded Ding! Dong! The Witch is Dead after -- frustrated and cynical about the recording industry in general, and their own lack of a hit record in particular --

vocalist Don Askew vouchsafed the notion that any song, properly presented, could become a hit. Challenged to prove it with a song — any song — from The Wizard of Oz, Askew approached the group, and keyboardist Wayne Wadhams worked up an arrangement based partly on Michael Praetorius' dance suite Terpsichore. [source]

Unfortunately for the Fifth Estate, the novelty nature of their chart success relegated them to the either the glory or the ignominy of one-hit-wonderdom.

The charts of the mid-to-late sixties were sprinkled with instrumentals (Mason Williams' Classical Gas, Booker T. and the MG's, Paul Mauriat's Love is Blue), movie themes (The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly; A Man And A Woman), a string of hits by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, and hit after hit written by Bert Bacharach. Casino Royale was all four at once, and remains a favorite of mine from that time in all four categories. It was a time when songs lived and died by their chord progressions, which were growing in sophistication (the venerable I/IV/V was joined by the VII -- e.g., B-flat in the key of C -- a lot of suspended fourths, and -- pardon my lack of training here -- whatever you get when you superimpose the V over the I), and the sound this arrangement pioneered found its way into everything from high-school band music to TV themes over the next few years. Although this only reached #27 on the national chart, Alpert and Bacharach would hook up a year or so later for a huge #1 vocal hit, This Guy's In Love With You.

The Choir

The Choir

It's hard to say why the memory of those few weeks is so strongly associated with this handful of songs, except for the fact that at the age of twelve, I was soaking up the pop music culture like a sponge; and that these songs all existed as equals on that jukebox, regardless of their respective chart success nationally. It might have also had to do with being temporarily suspended in time and place for a few weeks, a jukebox the only hint of the outside world and the rapid changes that were taking place in it.